by Hugh Semple

Between 2015 and 2018, Guyana held two local government elections. This was an impressive feat for a country which had only held village-level local government elections twice during the previous 45 years. Both the Afro-dominated PNC and the Indo-dominated PPP administrations regard local government elections as significant barometers of their political performance and refuse to allow such evaluations. As a result, local government itself is a very institution weak within the political structure of Guyana. In short, the current generation of Guyanese have very limited experience with local government.

The APNU/AFC coalition assumed power in 2015 with a renewed commitment to improve local government. The holding of local government elections twice between 2015 and 2018 is a reflection of their commitment to promoting this level of government. The coalition also conferred township status on three communities within the same period of time.

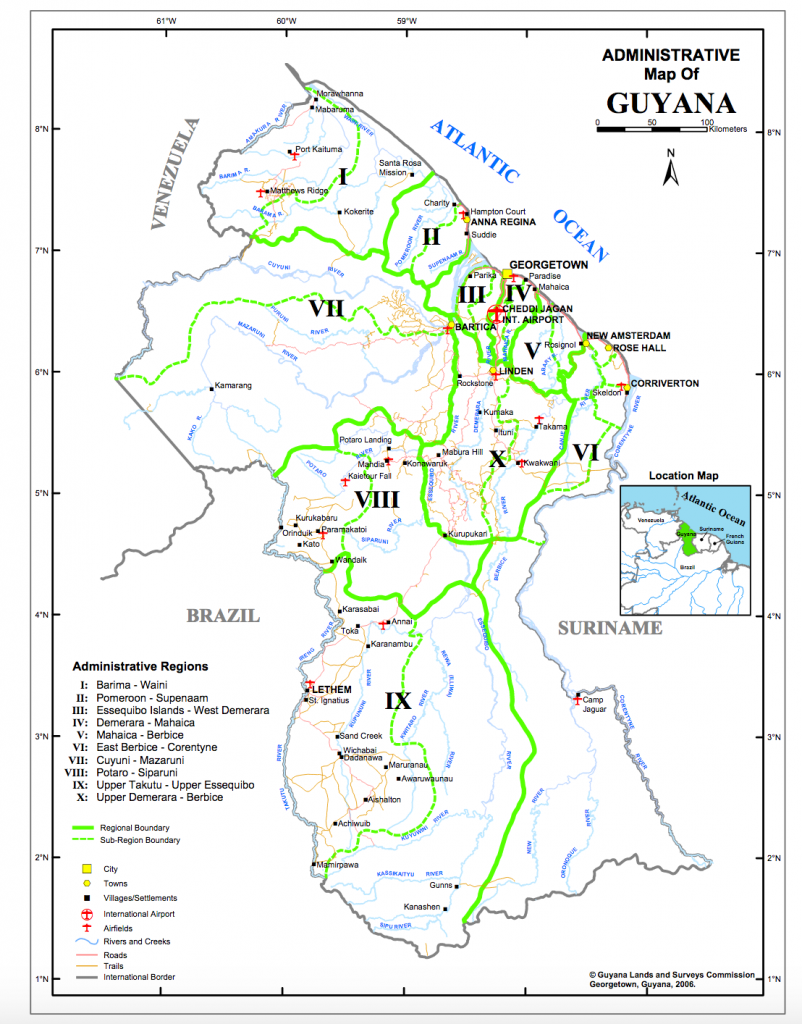

As is widely known, Guyana is sub-divided into ten administrative regions called Regional Democratic Councils (RDCs) (Figure 1). These Councils are responsible for implementing a significant proportion of the social and infrastructure budgets of Ministries within their council areas. They are typically engaged in repairing major roads and canals, maintaining or building new sea defenses, schools, health care facilities, etc. They also actively participate in the management of health, education, and police services within their jurisdictions.

Figure 1. Administrative Region of Guyana

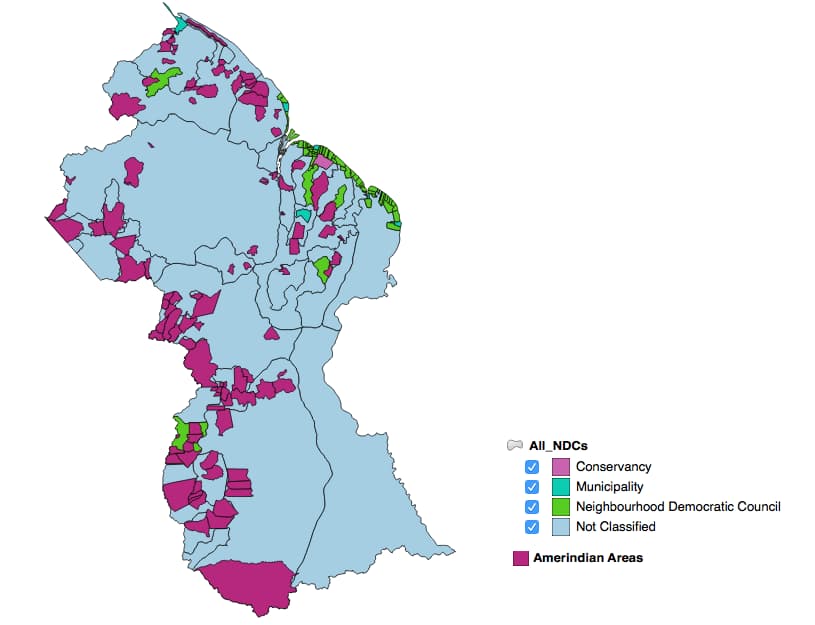

Each Regional Democratic Councils is subdivided into Municipalities, Neighborhood Democratic Councils, and Amerindian Villages (Figure 2). Municipalities are urban communities with city or town status. Thus, Georgetown, New Amsterdam, Linden, Rose Hall, Bartica, etc are all municipalities. Neighborhood Democratic Councils (NDCs) are essentially groups of nearby villages. The vast majority of NDCs are located on the narrow coastal plain where more than 90% of the country’s population resides. Amerindian villages are local government areas within the interior of the country. A large part of the country is neither NDCs nor Amerindian villages due to lack of population.

Figure 2. NDCs and Amerindian Villages, Guyana

NDCs and Amerindian village elections are required every three years, while elections for Regional Democratic Councils are required every five years at the time of the national elections. While elections for regional administrative councils have been held consistently, the same is not true for elections for NDCs and Amerindian villages. As mentioned earlier, for political expediency, Guyana does not have a strong tradition of holding these elections.

Villages

A cursory look at a map of Guyana shows that the coastal area, where most of the country’s population reside, is sub-divided into hundreds of tiny villages with average width of one-quarter of a mile and average length of 6 miles. These villages were the original coffee, cotton, and sugar plantations established by Dutch settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Historically, the plantations served as areas for both agriculture and residences and have evolved into the basic geographic unit of ‘village’ along the coast.

Outside of the home and immediate neighborhood, Guyanese who live in non-urban areas identify with the ‘village’. Family lands, either individually owned or “children property” are tied to the village, as do childhood memories of play, school, or any number of livelihood activities. Even among Guyanese who live overseas in London, New York, Toronto, or any number of places, an encounter with someone from their village is occasion of special fondness.

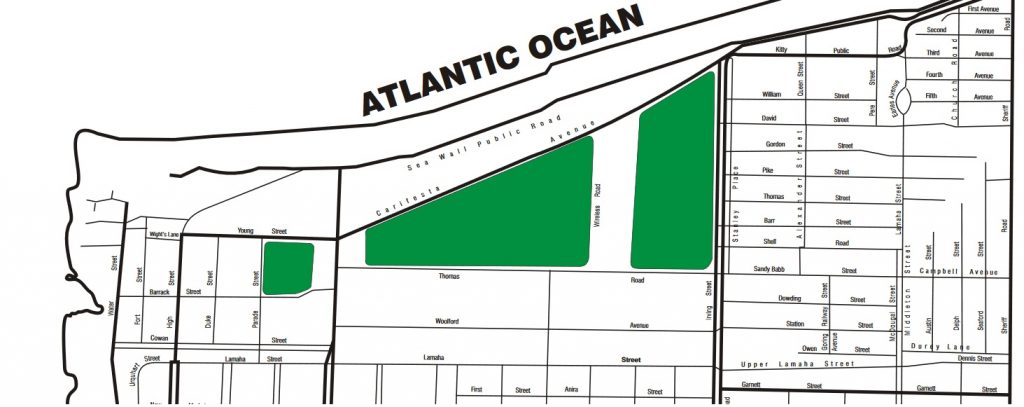

Figure 3. Villages on Guyana’s Coast

Given this strong sense of village attachment and identity, it is curious that current local government restructuring in Guyana has not sought to tap into these sentiments to help organize and manage people for local economic development. Indeed, until the 1970s, local government was organized around the village. Each village had a local council whose responsibility was to manage the various canals, sluices (kokers), and dams on which the village depended to survive the main environmental threat of flooding. Given the geography of Guyana’s coastal plain, these environmental constants have not changed. The land is still subjected to flooding from waters draining from the backlands, and because its average elevation is approximately six feet below high tide, flooding from the sea is still a constant worry.

Over the years, village-based local government had been abandoned because these units were deemed too small for effective environmental and socio-economic management. A fundamental argument was that these units resulted in too many unnecessary duplication of functions leading to higher administration costs and inability to reap economies of scale.

The first attempt at replacing village councils with larger units was made by President Forbes Burnham under Guyana’s new constitution in 1980. It called for a six-tier system with Regional Democratic Councils at the top of the system and five other types of local democratic councils below, excluding village councils (Regional Councils, sub-Regional Councils, District Councils, Community Councils, Neighborhood Councils, and People’s Cooperative Units,). Due to the top-heavy nature of this system, it was replaced by the current system in 2007, which only has two tiers. i.e, the Regional Democratic Councils at the top level and municipalities, NDCs, and Amerindian villages at the second level.

The Identity Problem of NDCS

A cursory examination of the boundaries of NDCs shows that they are combinations of nearby villages and their boundaries always follow the boundary of some village.

While NDCs appear to be reasonably-sized geographic units, it appears that one of their main issue is that people have weak emotional attachment to these units. Indeed, people seem to be aware that their village is part of an NDC, but they lack intuitive knowledge of the geographic extent of their NDC and how the NDCs are organized politically and administratively. The challenge facing local government officials is how best to integrate the strong coordinating role of NDCs with the historical and emotional attachments Guyanese have towards their villages.

One reason for strengthening the role of villages within NDCs is that it will negate recent calls by some political operatives to dispense with NDCs on the grounds that they are impersonal and insensitive to property rights and other development needs within individual villages1,2 . In the words of one Afro Guyanese leader, people have “lost control over their villages and more particularly over their lands and the lands are now subject to decisions by bodies called Neighbourhood Democratic Councils, many of which are alien to the people whose fore-parents purchased those lands and the people who still reside in those villages”.

It is further argued that Afro villages frequently find themselves located in NDCs dominated by people of Indian descent, who make land-use decisions that are contrary to the needs of the few Afro dominated villages within the NDCs. The reverse of this argument is also true. In a country dominated by race-based politics and administrative decisions, these arguments find resonance among many people. Clearly, additional attention should be given to the role of villages within NDCs

Better Integrating Villages into NDCs

One possible way of strengthening the role of villages within the current local government structure is to assign them the responsibility of administering a set of services that can be easily handled by these small groupings of people. Such services could include approval of land use and building applications, garbage collection, weeding of roads and canals, maintenance of playgrounds and burial grounds, etc. Currently, these functions are assigned to NDCs. In instances where villages are unable to perform these services, or do not want the responsibilities, then the NDC can continue to provide them.

To better differentiate between NDC and village functions, I advocate that NDCs be responsible for providing services that can be efficiently provided at the multi-village level. Such services could include maintenance of major dams, drains and canals, potable water supply, local climate change planning, and local economic development.

References

Denis Chabrol , May 2019. Afro-Guyanese pushing for return to village councils because NDCs have taken control.